Parcourir par catégorie

- L'alimentation

- L'archéologie

- L'économie du patrimoine

- L'environnement

- La communauté

- La communication

- Le design

- Le patrimoine autochtone

- Le patrimoine des femmes

- Le patrimoine francophone

- Le patrimoine immatériel

- Le patrimoine médical

- Le patrimoine militaire

- Le patrimoine naturel

- Le patrimoine Noir

- Le patrimoine sportif

- Les arts et la créativité

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Les objets culturels

- Les outils pour la conservation

- Les paysages culturels

- MonOntario

- Réutilisation adaptative

- Revoir le point de vue historique

- Page d'accueil

- L'alimentation

- L'archéologie

- L'économie du patrimoine

- L'environnement

- La communauté

- La communication

- Le design

- Le patrimoine autochtone

- Le patrimoine des femmes

- Le patrimoine francophone

- Le patrimoine immatériel

Le patrimoine immatériel

Le patrimoine culturel immatériel recouvre notamment la langue, les traditions, la musique, la nourriture et les compétences particulières.

- Le patrimoine médical

- Le patrimoine militaire

- Le patrimoine naturel

- Le patrimoine Noir

- Le patrimoine sportif

- Les arts et la créativité

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Les objets culturels

- Les outils pour la conservation

- Les paysages culturels

- MonOntario

- Réutilisation adaptative

- Revoir le point de vue historique

Revoir le point de vue historique

Cette réflexion s’inscrit dans un discours plus vaste sur le point de vue historique adopté, sur le genre, les personnes de couleur et les groupes marginalisés sur le plan économique, et sur les autres communautés dont l’histoire est ignorée ou volontairement passée sous silence dans le discours officiel.

The new St. Brigid’s

St. Brigid’s Catholic Church in Ottawa has entered a new era. For almost 120 years, it has stood at the heart of a diverse and dynamic neighbourhood not far from Parliament Hill. Its builders, ministers and parishioners came from the immigrant stock that occupied the tenements of Lowertown and worked in the mills that belonged to the Protestant power-elite of Upper Town. As ownership now passes from the diocese to a group of cultural enthusiasts, the new St. Brigid’s Centre for the Arts and Humanities will become a magnet for the throngs of young, hip and moneyed Ottawans who are settling in this now-diverse quarter.

The Catholic diocese of Ottawa (then Bytown) was established by Pope Pius IX in 1847 to serve the growing population of French Canadians and Irish in the city, many of whom had migrated to the area as labourers on the Rideau Canal. In 1853, the Cathedral of Notre Dame was dedicated; it became the principal place of worship in the city. Other parishes were established in Upper Town and two French-speaking churches were built in the vicinity of the cathedral. In 1888, Archbishop Duhamel agreed to a secession of English-speaking parishioners from the cathedral to establish the parish of St. Brigid’s nearby.

The Romanesque Revival church – designed by Ottawa native James R. Bowes – incorporates many styles, as was common in the late Victorian era. Reflecting the modest means of the parish, the church was also constructed of heavy limestone blocks instead of more elaborate stonework. It is fitting that the structure was dedicated to St. Brigid, the patroness of Ireland, as its sparely adorned exterior is reminiscent of Ireland’s fortified churches.

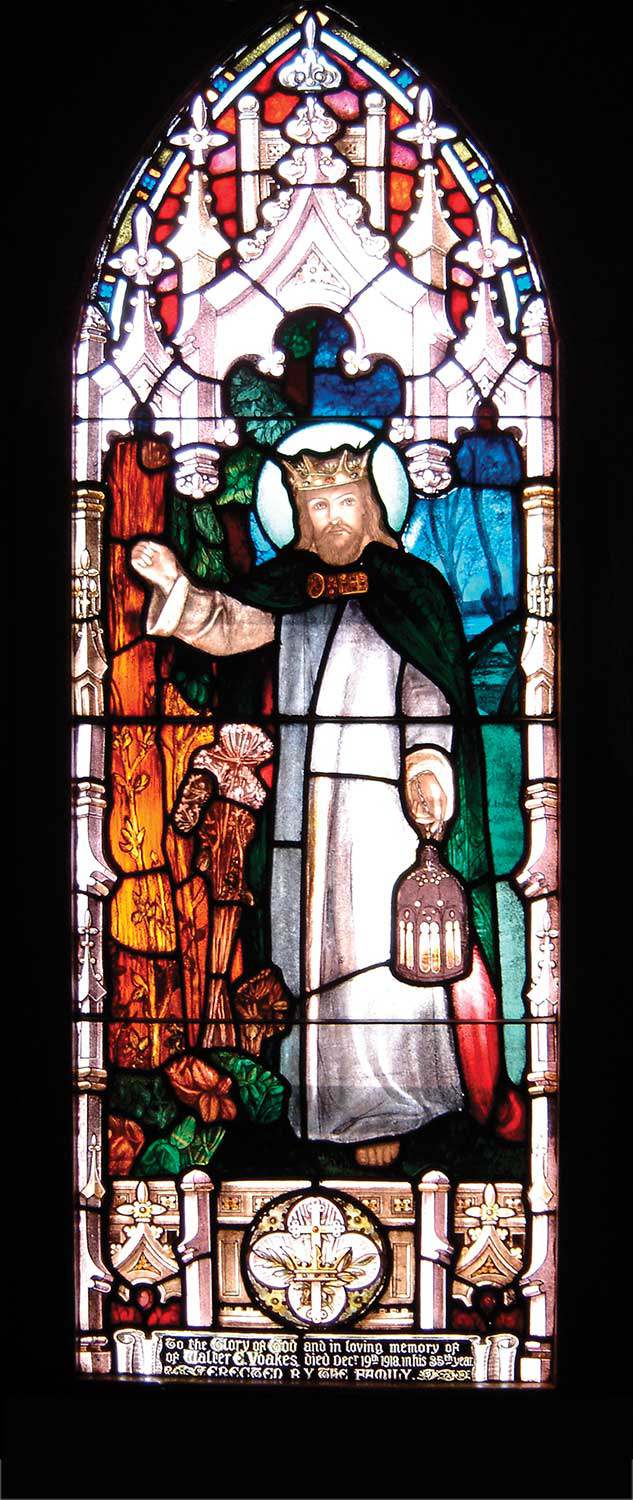

The interior is truly a study in contrasts. On the one hand, the layout is simple. The nave is divided in three, with two side aisles flanking the centre one. On the other hand, the ceilings of the side aisles offer rare fan-vaulted construction, decoratively painted and adorned with pendants. Generous pews of carved ash and walnut receive parishioners, and elaborate painted altarpieces decorate the chancel. Orme and Sons of Montreal installed the magnificent symbol-laden stained glass windows. Irish motifs, such as the harp and shamrock, adorn the gilded pipes of the enormous 1910 Casavant organ in the choir loft.

The real treasure of St. Brigid’s, however, came later in its history. In 1908, an ambitious program of interior painting was undertaken by Toussaint-Xenophon Renaud. The Quebecois painter had a prolific career, painting nearly 200 ecclesiastical interiors throughout Quebec and the Ottawa Valley. There are murals of the Nativity, the Descent from the Cross and depictions of the Immaculate Conception and St. Joseph. Renaud also decorated the wooden columns to resemble marble and created an extensive program of polychromy, stenciling and gilding. The whole interior was whitewashed in the 1960s, and only the murals above the main and side altars have been restored.

The church quickly became a focal point for the local Irish population. Until 1895, the Christian Brothers educated young men, while the Grey Sisters did the same for girls. By the time of its 50th anniversary in 1939, the parish offered numerous organized activities, including choirs, service groups and athletic teams. The Society of St. Jerome sewed clothing for the poor and St. Brigid’s Young Men’s Association fielded teams in hockey, football, track and field, lacrosse and baseball. Notable National Hockey League alumni Alex Connell, Edwin Gorman and King Clancy honed their skills on these teams.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the demographics of St. Brigid’s changed. The owner of the church – the Archdiocese of Ottawa – like many dioceses in Ontario, has undergone a property rationalization in recent years. In April 2006, Archbishop Marcel Gervais announced that St. Brigid’s would close due to the escalating costs of maintaining the aging building. In September 2007, the last mass was celebrated in the church and it was deconsecrated.

In October that same year, the building was purchased by a non-profit group to convert the space into a cultural venue. The building is protected by a municipal designation and a provincial conservation easement – the elements that make St. Brigid’s such an important building will be preserved. Renamed St. Brigid’s Centre for the Arts and Humanities, it is the home of the National Irish Canadian Cultural Centre. Its new owners have filled its schedule with events both Irish-focused and cross-cultural. Even as its religious purpose has ended, its important social function is as strong as ever. St. Brigid’s continues to fulfil the diverse cultural needs of the new Lowertown.

histoiresconnexes

- 05 févr. 2026

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Elizabeth Papadopoulos,

La réutilisation adaptative : Bâtir autour du point de vue d’un architecte

Leroy Shum, architecte de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien, nous parle des éléments clés de la réutilisation adaptative, des nouvelles tendances de l’industrie et des...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : David Leonard,

Comment Portes ouvertes Ontario stimule les collectivités de la province

Le programme Portes ouvertes Ontario de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien collabore avec des collectivités et des partenaires afin de rendre accessibles les sites culturels...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

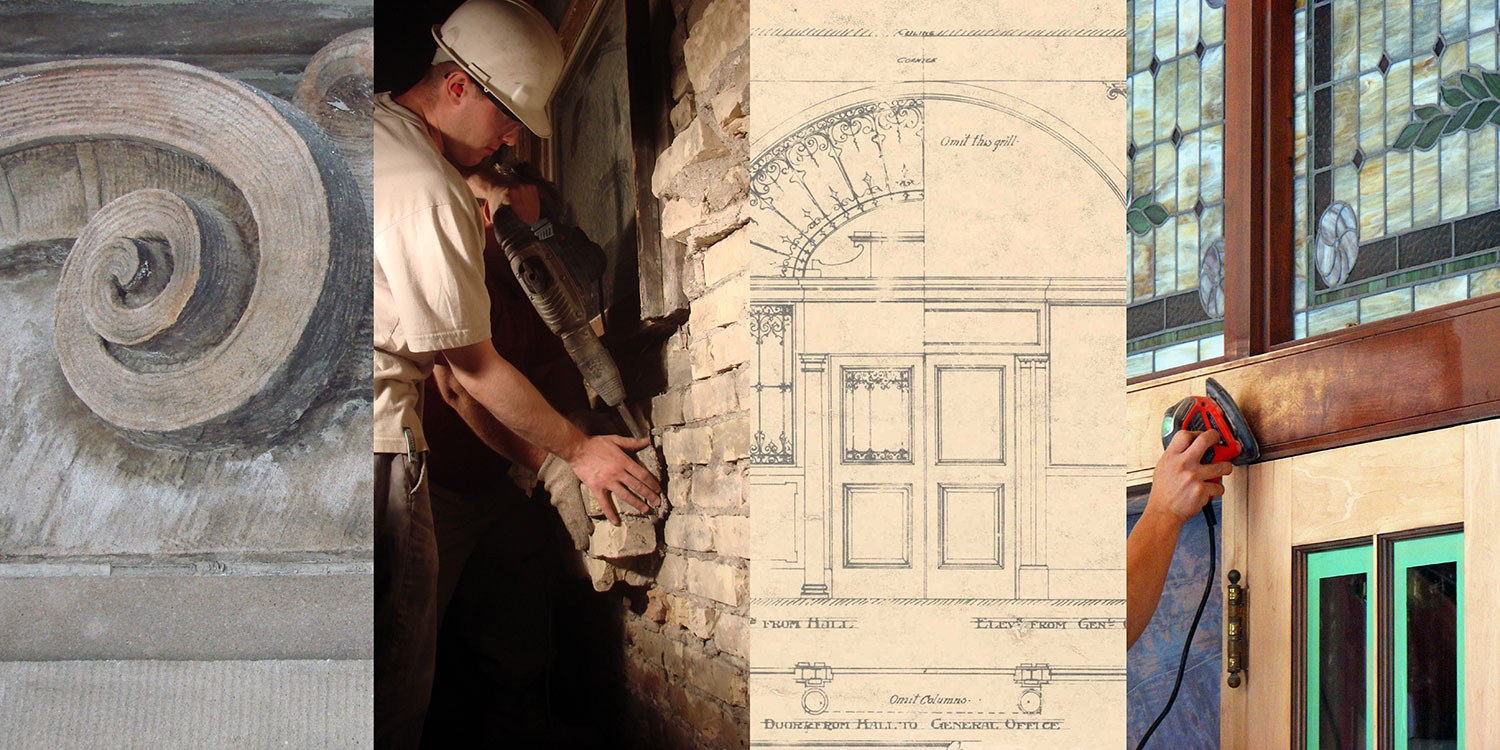

Éloge du génie artisanal

L’un des plus grands plaisirs qu’implique d’œuvrer à la conservation du patrimoine architectural ontarien, est la possibilité de travailler avec des matériaux de construction traditionnels...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Christina Jennings,

Silence, on tourne!

Shaftesbury est la société de production à qui l’on doit les séries télévisées à succès Les Enquêtes de Murdoch et Frankie Drake : Détective privée...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Emily Sajdak,

L’effet de halo économique : des méthodes novatrices pour évaluer l’impact des lieux sacrés sur la société

Nichée dans la vieille ville de Philadelphie, en Pennsylvanie, l’église historique Old St. George’s, de l’Église méthodiste unie est une « église fondatrice » de...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Erin Semande,

Étude de cas : le tunnel ferroviaire de Brockville (Brockville)

Emplacement : 1 Block House Island Road, BrockvillePropriétaire : Ville de BrockvillePartenaires : Brockville Railway Tunnel Committee (ainsi que de nombreux généreux donateurs)Vocation historique ...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

L'alimentation

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Erin Semande,

Étude de cas : Brasserie-restaurant Mudtown Station (Owen Sound)

Adresse : 1198, 1re Avenue Est, Owen SoundPropriétaire : Ville d’Owen SoundPartenaires : Famille Kloeze (Mudtown Station Inc.)Fonction initiale : Gare ferroviaire d’Owen Sound (Chemin...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : John Coleman,

Les leçons du passé

Le patrimoine figure depuis toujours au cœur d’un projet ambitieux de l’Université de Windsor : celui de préserver le manège militaire de la ville, vieux...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Gail Lord,

Musées et patrimoine : le pouvoir de convaincre au service du mieux-vivre

Les musées et le patrimoine architectural sont les moteurs de la réhabilitation et de la revitalisation des villes. L’agence Lord Cultural Resources a mis ses...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Michael Emory,

La place des édifices patrimoniaux dans l’évolution des espaces de travail

Je travaille chez Allied Properties, un grand propriétaire, gestionnaire et promoteur de locaux professionnels en milieu urbain implanté dans les principales villes du Canada. Les...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Kiki Aravopoulos,

Étude de cas : Palais de justice du district de Thunder Bay

Adresse : 277, rue Camelot, Thunder BayPropriétaire : David Sun, entrepreneur/investisseurPartenaires : Ascend HotelsFonction initiale : Palais de justiceEmploi actuel : Hôtel et centre de...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Jennifer Campbell,

À Kingston, le patrimoine dynamise la collectivité et l’économie culturelle

En 2010, la ville de Kingston publiait son premier plan pour la culture (Culture Plan) – un document qui dévoile une démarche raisonnée, authentique et...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Paul Shaker,

La valeur économique des quartiers patrimoniaux : comparaison de la hausse des taux d’imposition entre les districts de conservation du patrimoine et les zones non désignées de la ville de Hamilton

Plusieurs visions s’opposent lorsqu’il s’agit d’évaluer les biens patrimoniaux. D’un côté, la valeur esthétique et économique des édifices patrimoniaux en milieu urbain fait désormais l’unanimité...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Clare Ronan,

Reside : Quand la conservation du patrimoine ouvre la porte au logement abordable

Chef de file en matière de prévention de l’itinérance à l’échelle nationale, Chez Toit est un organisme de bienfaisance canadien à l’origine de diverses initiatives...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Thompson M. Mayes,

Les lieux anciens soutiennent une économie solide, durable et prospère

Dans mon ouvrage intitulé Why Old Places Matter, je me suis attaché à présenter les nombreuses raisons expliquant pourquoi les lieux anciens aident les personnes...

- 01 oct. 2019

- L'économie du patrimoine

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Beth Hanna,

Revitaliser les collectivités – Le pouvoir de la conservation

Ces dernières années, j’ai abondamment parlé et écrit au sujet de la valeur – pour évoquer ce que nous choisissons de protéger, comment nous prenons...

- 17 févr. 2017

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

MonOntario - Auteur : Kevin Mannara,

Ce qui était et ce qui sera

Le terme symbolkirchen pourrait approximativement être traduit comme une « église porteuse de symboles ». De telles églises évoquent des réalités qui nous dépassent. Elles...

- 17 févr. 2017

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

MonOntario - Auteur : Georges Quirion,

La riche histoire industrielle de l’Ontario

Le Nord de l’Ontario possède des structures uniques, généralement méconnues, dispersées dans des petites communautés. Riches en histoire, elles constituent de précieuses ressources pour de...

- 17 févr. 2017

- Le patrimoine autochtone

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

MonOntario - Auteur : R. Donald Maracle,

Christ Church, la chapelle royale de Sa Majesté chez les Mohawks en territoire mohawk de Tyendinaga

Durant la Révolution américaine, les Mohawks ont été forcés d’abandonner leurs terres dans le nord de l’État de New York. En 1784, après avoir passé...

- 05 déc. 2014

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Valerie Verity,

L’histoire de deux familles

Quelle histoire que celle racontée par la maison Macdonell-Williamson!! Son emplacement – elle jouit d’un impressionnant point de vue sur la rivière des Outaouais (sur...

- 05 déc. 2014

- L'archéologie

Les bâtiments et l'architecture - Auteur : Dena Doroszenko et Romas Bubelis,

Différentes perspectives d’un même site : artéfacts, fragments et couches

Lorsque la Fiducie œuvre à la conservation d’une propriété aussi complexe que la maison Macdonell-Williamson, elle examine le site dans sa dimension d’artéfact sous plusieurs...

- 05 déc. 2014

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les objets culturels - Auteur : Sam Wesley,

L’interprétation de la maison Macdonell-Williamson au travers de quatre artéfacts

Il est tentant, en admirant les murs de pierre vieux de plusieurs siècles, la splendeur palladienne et le cadre pittoresque de la maison Macdonell-Williamson, d’évoquer...

- 05 déc. 2014

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Michael Csiki, Majula Koita et Chantel Godin,

Une solution de génie : perspective structurale de la maison Macdonell-Williamson

Pour les ingénieurs de chez Quinn Dressel Associates, la réhabilitation structurale de la maison Macdonell-Williamson a constitué une formidable occasion de contribuer à la préservation...

- 14 févr. 2014

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Janet Gates,

Cent ans de divertissement

Les anniversaires sont prétexte à festoyer et, dans le cas des théâtres torontois Elgin et Winter Garden, à porter un toast à 100 ans d’histoire...

- 06 sept. 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité - Auteur : Erin Semande,

Partenariat de conservation

La Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien dispose d’un certain nombre d’outils de conservation pour protéger et préserver le patrimoine à l’échelle de la province. Les servitudes...

- 06 sept. 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Thomas Wicks,

Faire du théâtre

Les salles de spectacle revêtent une importance considérable dans les collectivités de l’Ontario. Elles traduisent les aspirations de leurs concepteurs et témoignent de l’évolution de...

- 06 sept. 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Pamela Cain,

Deuxième rappel : un nouveau départ pour un théâtre ontarien

Depuis le début des années 1970, la troupe du Magnus Theatre de Thunder Bay a pris le parti de la rénovation urbaine, du réemploi et...

- 06 sept. 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité - Auteur : Wayne Kelly, Romas Bubelis, Brett Randall et Beth Hanna,

Perspectives : Le centenaire du théâtre Elgin

Rétrospective par Wayne Kelly En 1912, lorsque Marcus Loew, entrepreneur dans le secteur du théâtre, implante sa société, Loew’s Theatrical Enterprises, à Toronto, il imagine...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

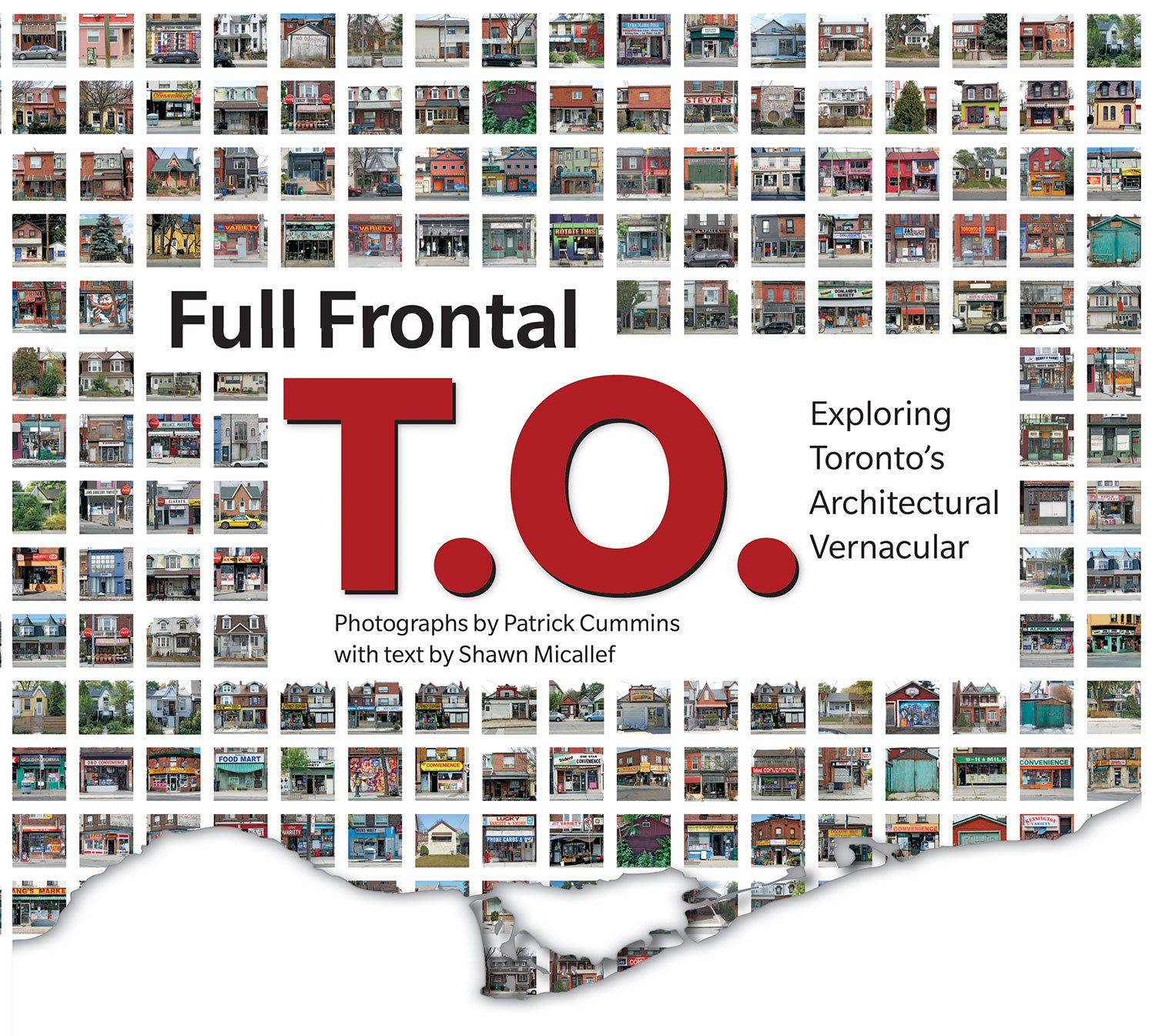

Ressources : Édifier des communautés : les districts de conservation du patrimoine

À l’affiche sur les étagères Full Frontal T.O. – Exploring Toronto’s Architectural Vernacular, par Shawn Micallef, photographies de Patrick Cummins. Coach House Books, 2012. Depuis...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Jim Leonard,

Les districts de conservation du patrimoine : l’outil le plus populaire de la trousse d’information sur le patrimoine?

Lorsque la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario est entrée en vigueur en 1975, les municipalités de toute la province ont tout à coup eu...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Mark Warrack,

L’évolution des districts

Meadowvale Village – jadis petit village rural – se situe sur la rivière Credit, à l’extrémité nord de la ville de Mississauga. À la fin...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Joan Mason,

Patrimoine local : les intendants de New Edinburgh

Située dans la ville d’Ottawa, à la confluence de la rivière Rideau et de la rivière des Outaouais, New Edinburgh est une collectivité historique dont...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Stephen Ashton,

Les personnes qui s’investissent dans la conservation du patrimoine

Ayant grandi à Port Hope, j’étais convaincu que toutes les collectivités disposaient d’une fabuleuse rue principale. Ce n’est qu’une fois étudiant à l’université, lors d’un...

- 10 mai 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Denise Van Amersfoort,

L’histoire de Goderich : une leçon de survie

Depuis un an et demi, la rue West de Goderich est à la fois un chantier de construction et un espace de services et de...

- 15 févr. 2013

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité - Auteur : Bruce Beaton,

Drôles de murs

L’art de conter des histoires puise son inspiration à de nombreuses sources. Traditionnellement, les musées tissent une narration à partir d’objets réels : un vase...

- 12 oct. 2012

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : David Nattress,

Assurer la vivacité du patrimoine agricole ontarien

Notre monde en expansion constante offre moins de terres arables pour cultiver les aliments nécessaires à notre survie. Avec la disparition des fermes observée en...

- 31 mai 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Thomas Wicks,

Le patrimoine dans le domaine public : L’ancien fait peau neuve

L’Ontario est en pleine croissance démographique. Les municipalités de la province ne cessent de croître, tout comme le besoin de revitaliser les installations municipales existantes...

- 31 mai 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Le patrimoine naturel

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Sean Fraser, Erin Semande et Mike Sawchuck,

Les investissements en matière de conservation

Force est de constater que les démarches de conservation de notre patrimoine restent l’exception et non la règle. L’approche sensée consistant à vivre selon ses...

- 31 mai 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Wayne Kelly,

Les racines de la démocratie : les édifices du premier Parlement de l’Ontario

À l’approche du bicentenaire de la guerre de 1812, l’effervescence se fait de plus en plus sentir sur le site des édifices du premier Parlement...

- 28 janv. 2011

- Le patrimoine des femmes

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Catrina Colme,

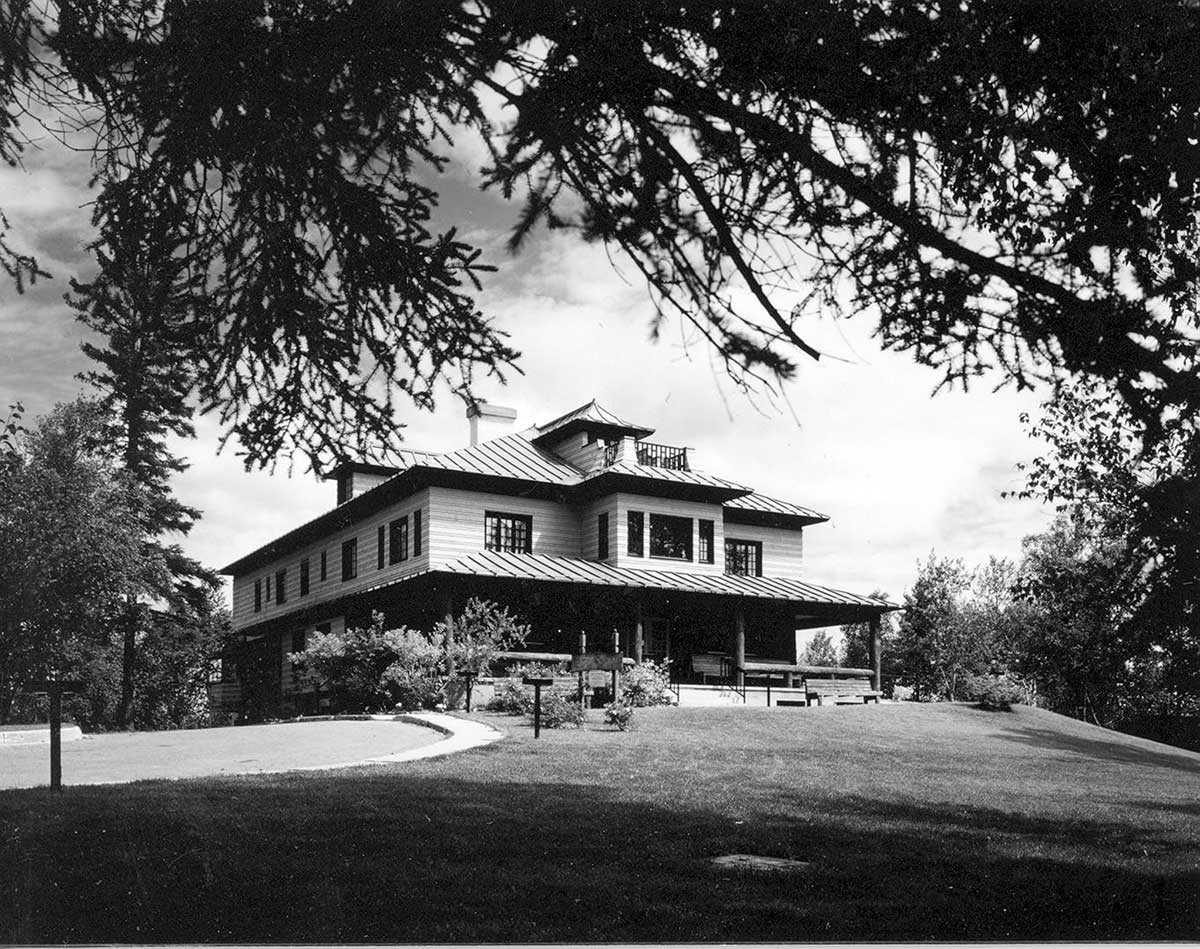

La propriété de Doris McCarthy, « Le paradis d’une folle », continuera d’inspirer les générations d’artistes à venir

Avec le décès de Doris McCarthy le 25 novembre 2010, le Canada a perdu l’une de ses artistes de talent et de renom, notamment connue...

- 28 janv. 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Michael Eamon,

Au cœur des Kawarthas

La première fois que vous visiterez l’imposant hôtel de ville de Peterborough, n’oubliez pas de regarder par terre. Inspirée par le mouvement « City Beautiful...

- 28 janv. 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Barb McIntosh,

La maison-musée historique de Peterborough

La maison Hutchison possède une place à part dans l’histoire sociale de Peterborough. Des bénévoles locaux ont construit cette demeure en 1836 pour convaincre l’un...

- 28 janv. 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Jim Leonard,

Se relever après une catastrophe naturelle

Dans l’après-midi du 14 juillet 2004, les nuages crèvent au-dessus de la ville de Peterborough. Pendant tout le reste de la journée, la soirée et...

- 28 janv. 2011

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Dennis Carter-Edwards,

À la découverte de la voie navigable Trent-Severn

Il aura fallu 87 ans pour construire la voie navigable Trent-Severn, qui étire aujourd’hui ses 386 kilomètres en plein cœur de la province et relie...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

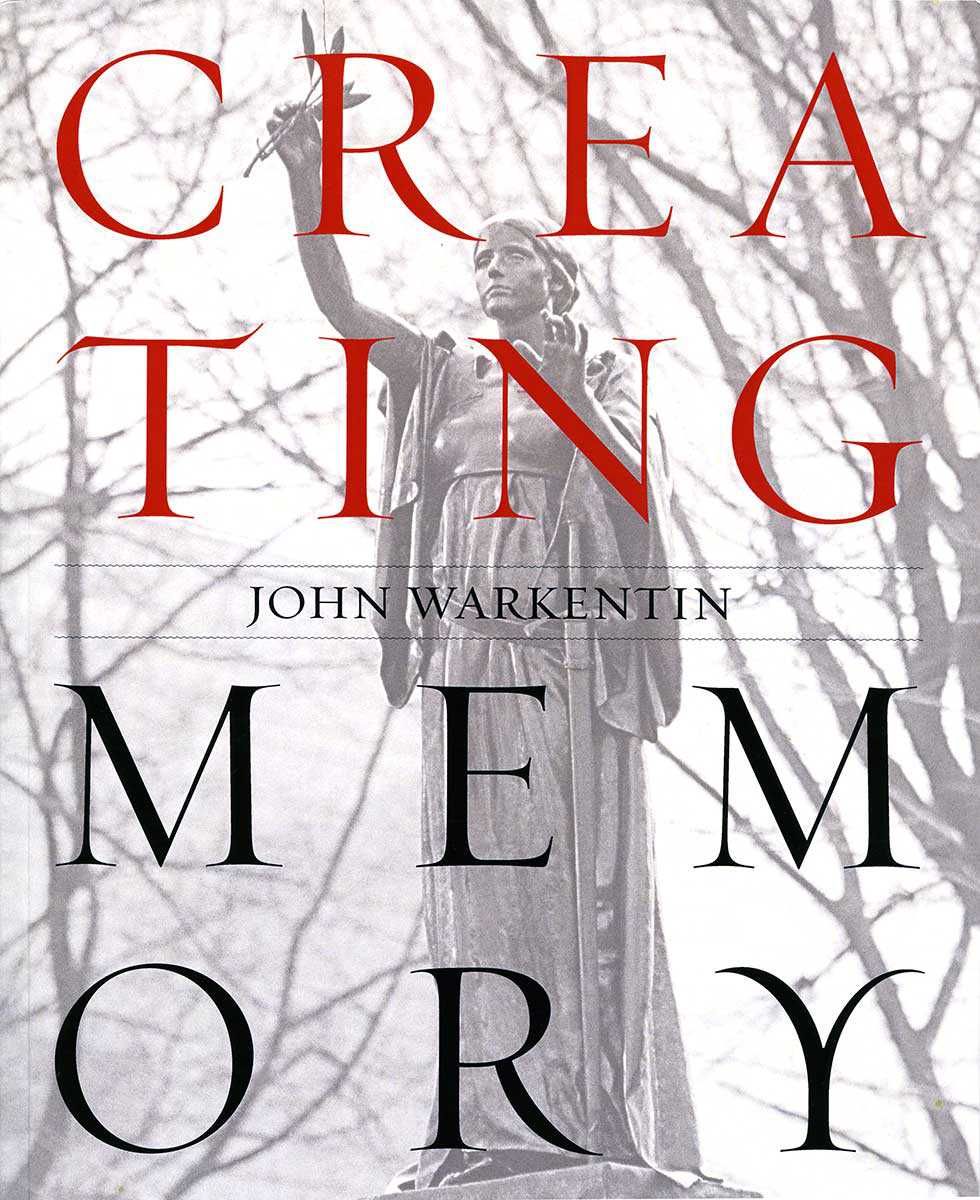

Ressources : Nous situer dans l’histoire de l’Ontario

À l’affiche sur les étagères Creating Memory, par John Warkentin Becker Associates, 2010. Toronto compte plus de 6 000 sculptures publiques installées à l’extérieur, des...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Regan Hutcheson et Leah Wallace,

Désignations par regroupement

Comprendre Unionville, par Regan Hutcheson Visiter Unionville, c’est comme remonter le temps. Située au nord de Toronto, au centre de Markham, Unionville est l’une des...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Sally Coutts,

Un exemple à suivre

Les petites et les grandes villes ontariennes désignent des biens aux termes de la Partie IV de la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario depuis...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Dave Benson,

Catalogage du patrimoine d’une collectivité

Chatham-Kent est une municipalité issue d’une fusion et comprend de nombreux établissements anciens constituant un patrimoine qui compte des milliers de bâtiments. Récemment, Heritage Chatham-Kent...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Jim Leonard,

Une journée peut faire toute la différence

Le 11 mars 2009, le conseil municipal de Brampton a désigné 17 biens aux termes de la partie IV (article 29) de la Loi sur...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Sur les traces des Olmsted en Ontario

Un patrimoine d’une richesse insoupçonnée, laissé par les architectes paysagistes Charles et Frederick Olmsted Jr, se manifeste à travers des fragments de paysage dans l’ensemble...

- 06 mai 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

La préservation d’un trésor national

Le Centre des salles de théâtre Elgin et Winter Garden de Toronto est un bâtiment replié sur lui-même, qui est doté d’une architecture intérieure. Par...

- 11 févr. 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Evelyn G. McLean,

Walkerville : le patrimoine d’une ville de compagnie

Walkerville figure au nombre – de plus en plus réduit – des villes de compagnie du XIXe siècle. Elle fait partie de la ville de...

- 11 févr. 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Kiki Aravopoulos,

Une promesse de jours meilleurs

La gare de St. Thomas de la Compagnie de chemin de fer du Sud du Canada (CCSC) occupe une place prépondérante dans la rue principale...

- 11 févr. 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Kathryn McLeod,

Exploration de la péninsule méridionale de l’Ontario

Lorsqu’on se promène le long des routes et des cours d’eau de la péninsule méridionale de l’Ontario, c’est toute une mosaïque d’histoires qui s’offre à...

- 11 févr. 2010

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les paysages culturels - Auteur : Dave Benson,

L’histoire de Chatham-Kent

Le très riche patrimoine culturel de Chatham-Kent remonte à bien avant la colonisation européenne. Il s’est constitué lorsque d’immenses villages entourés de palissades et les...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Alison Little,

Un héritage humanitaire : les groupes confessionnels, acteurs sociaux en Ontario

Porter assistance aux personnes dans le besoin fait depuis longtemps partie de la tradition religieuse en Ontario. Des groupes d’origine confessionnelle offrant une aide médicale...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Jennifer Drinkwater,

Les synagogues de Toronto : entretenir les mémoires collectives

La mémoire collective est une mémoire culturelle : c’est ce qui est inscrit dans la mémoire d’un groupe social ou culturel ayant vécu un certain...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

Ressources sur les lieux de culte

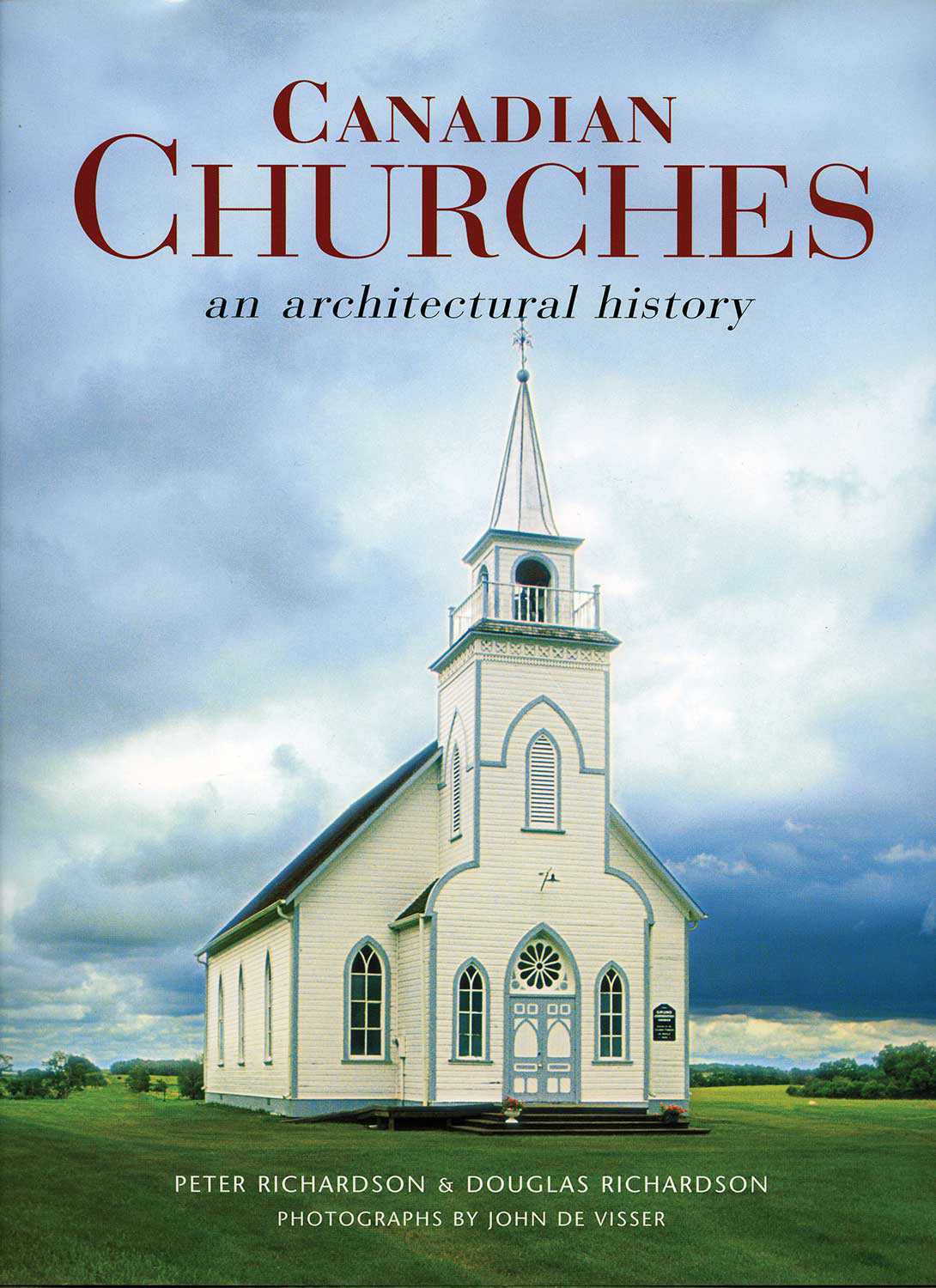

Publications Churches: Explore the symbols, learn the language and discover the history, par Timothy Brittain-Catlin Collins Press. Les églises et les cathédrales, délibérément imposantes et...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Marybeth McTeague,

Lieux de culte de l’après-guerre en Ontario : des conceptions modernistes évoquant des styles traditionnels

Les années qui suivirent la Seconde Guerre mondiale se caractérisèrent par un sentiment de renouveau et d’optimisme. Les lieux de culte édifiés en Ontario au...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Jennifer Laforest,

La conservation intégrée des lieux de culte

La conservation intégrée des édifices religieux peut à la fois permettre de conserver certains sites patrimoniaux importants et bénéficier aux collectivités, mais en Ontario, les...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Candace Iron et Malcolm Thurlby,

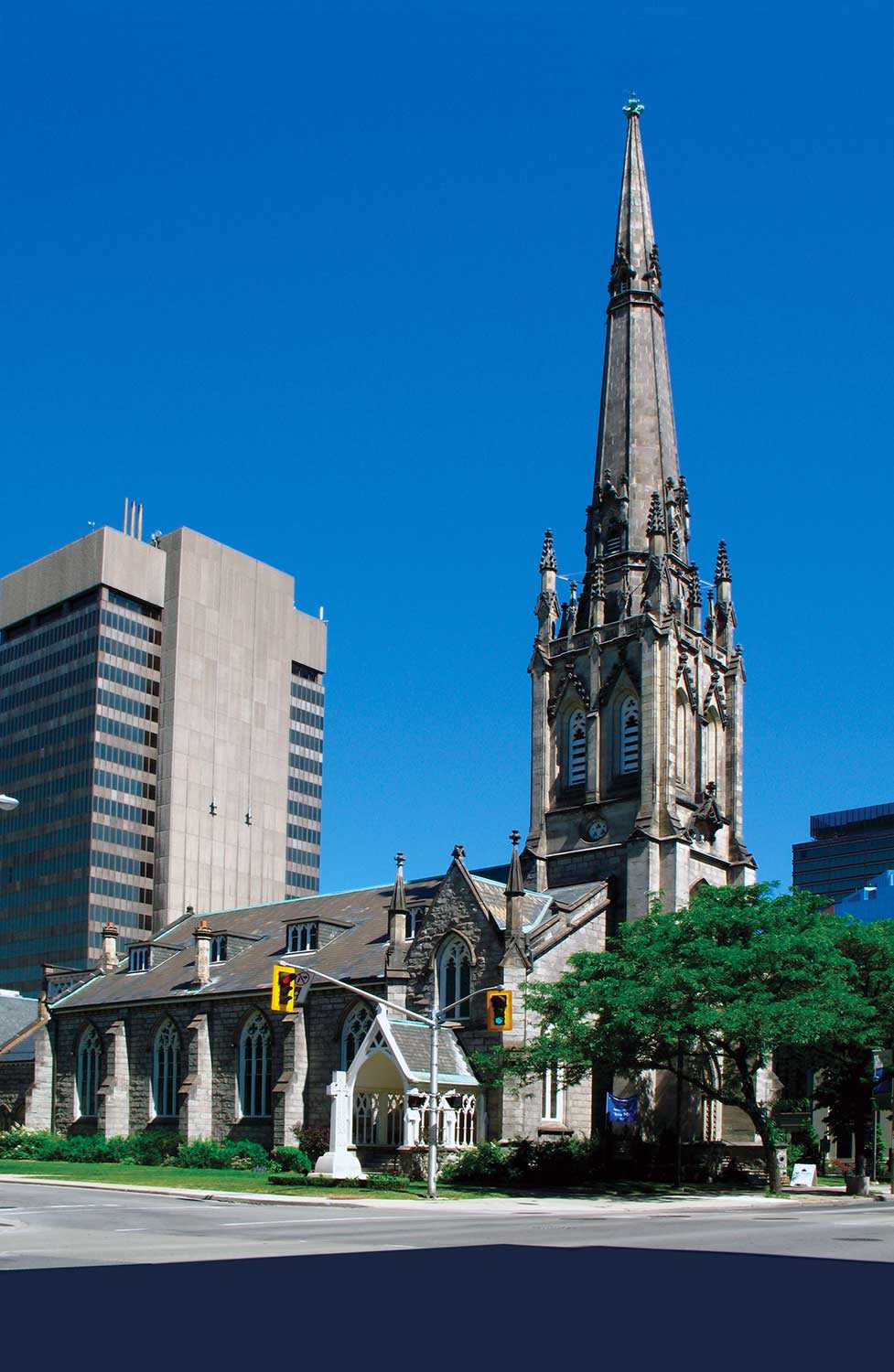

Traditions gothiques dans les églises ontariennes

L’importance du culte dans l’Ontario du XIXe siècle transparaît dans les églises érigées dans la province au cours de cette période. Invariablement, les confessions religieuses...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : David Cuming,

Une perspective municipale : le cas de Hamilton

Les lieux de culte sont souvent des bâtiments remarquables, construits, grâce à des techniques et matériaux spécialisés, dans des formes et des styles existant depuis...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité - Auteur : Nicholas Holman,

La musique du culte

« L’architecture est une musique figée », a dit Goethe, mais pourquoi de tels propos? Était-ce parce que les intérieurs des églises chrétiennes, avec leurs...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité - Auteur : Erin Semande,

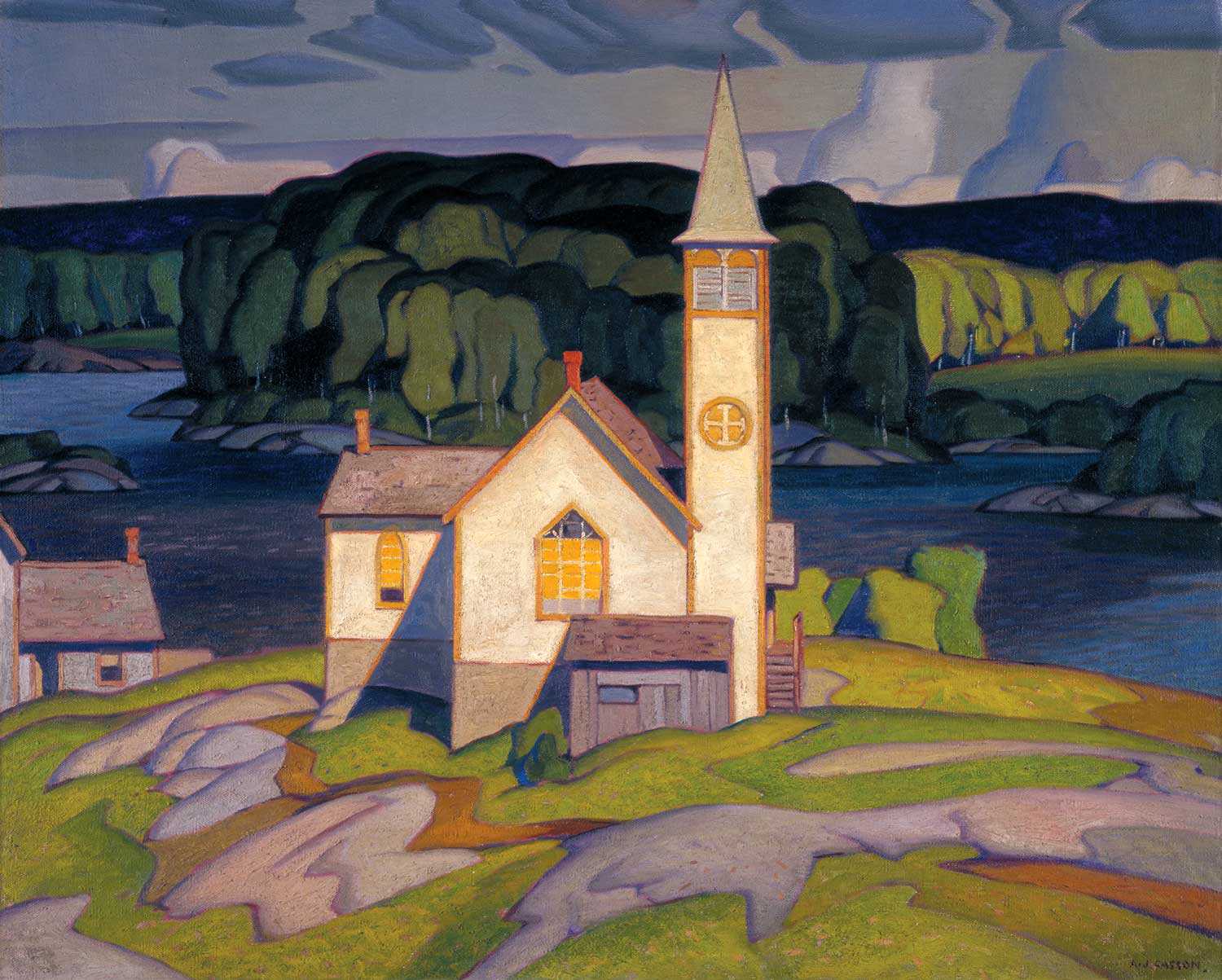

L’œuvre du Groupe des sept : l’art dans l’église, l’église dans l’art

Depuis des siècles, des artistes renommés se sont vus confier la décoration intérieure des lieux de culte, où leur talent transforme bien souvent un simple...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Vicki Bennett,

Structure et fonction : l’impact de la liturgie, du symbolisme et de l’usage sur la conception architecturale

Au cours du XIXe siècle, l’emplacement, l’état matériel et les mérites stylistiques des églises constituaient aux yeux du public des indicateurs fiables de la valeur...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Jane Burgess et Ann Link,

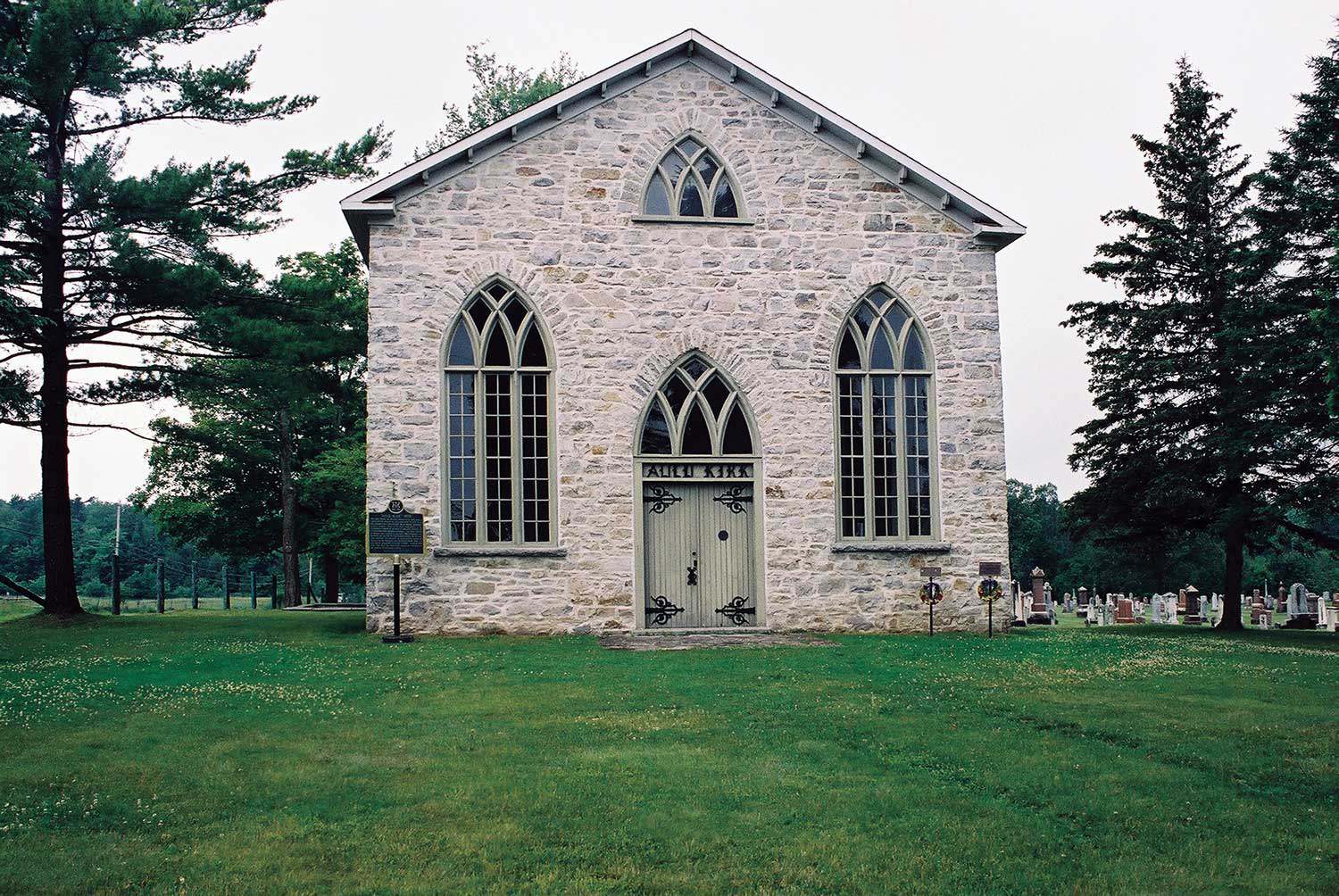

Une intendance durable préserve une précieuse église patrimoniale

Située juste à l’est de Beaverton, Old Stone Church, édifiée en 1840 par une congrégation essentiellement écossaise, est une petite église géorgienne simple mais aux...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Laura Hatcher,

La physionomie changeante du culte

Le style architectural d’un lieu de culte, tout comme ses proportions intérieures, les matériaux employés et ses pierres de date, constituent autant d’indices de l’histoire...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Le patrimoine Noir

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Steven Cook et Wilma Morrison,

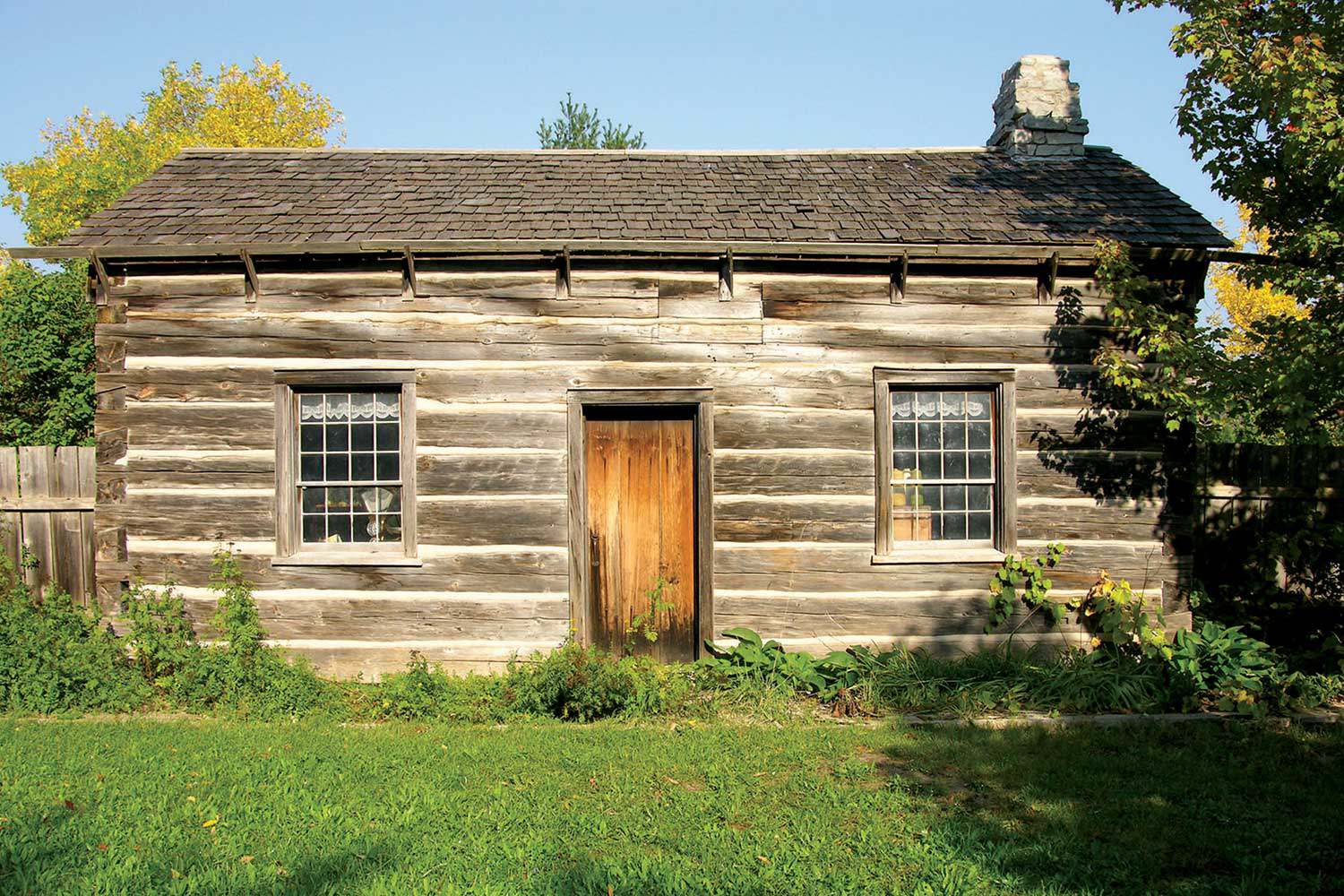

Liberté religieuse sur la terre promise

Eli Johnson travaillait sans relâche dans des plantations de Virginie, du Mississippi et du Kentucky avant de tenter sa chance sur la « terre promise...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les paysages culturels - Auteur : Wendy Shearer,

Les lieux de culte dans les paysages culturels de l’Ontario rural

Les paysages culturels du Sud rural de l’Ontario recèlent une myriade de ressources patrimoniales, tant du point de vue de l’environnement naturel que du patrimoine...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Le patrimoine autochtone

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Yves Frenette2,

Églises du « Nouvel-Ontario »

Au milieu du XIXe siècle, le Nord de l’Ontario est resté très semblable à ce qu’il était sous le régime français – une région de...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Le patrimoine autochtone

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Le patrimoine francophone

La communauté - Auteur : Wayne Kelly,

Le riche patrimoine religieux de l’Ontario

Depuis les peuples autochtones qui, durant des milliers d’années, ont célébré des cérémonies religieuses et culturelles dans des sites qui revêtaient, à leurs yeux, une...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Le patrimoine autochtone

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les objets culturels - Auteur : Kathryn McLeod,

Christ Church et l’argenterie de la reine Anne

Située sur le Territoire Mohawk Tyendinaga dans la baie de Quinte, Christ Church abrite un service de communion en argent qui date de 1712. Ce...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les paysages culturels - Auteur : Marcus R. Létourneau,

Les paysages sacrés dans les communautés ontariennes

Les lieux de culte constituent un aspect visible du patrimoine de l’Ontario, mais ils s’inscrivent également dans un panorama culturel bien plus vaste pour inclure...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Richard Moorhouse,

Lancement de l’inventaire des lieux de culte

Enquêter, se documenter et chercher sont les premières étapes du processus de conservation. Comment pourrait-on prendre des décisions concernant notre patrimoine sans avoir acquis au...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Les objets culturels - Auteur : John Wilcox,

Aventures en lumière et en couleur

La lumière est un aspect fondamental de toute l’architecture, surtout dans les lieux de culte. La lumière a toujours été considérée comme une manifestation de...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Bruce Pappin,

Le défi du changement dans le diocèse catholique de Pembroke

En mai 2006, la paroisse catholique de Ste Bernadette, dans la petite collectivité du Nord de l’Ontario de Bonfield, a célébré le 100e anniversaire de...

- 10 sept. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Les problèmes inhérents à la propriété

Les lieux de culte historiques peuvent posséder une valeur en termes de patrimoine culturel qui est à l’origine d’un soutien public en faveur de leur...

- 28 mai 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Subventionner la démolition

Dans la nature, rien ne se perd. Le règne naturel obéit à une organisation cyclique dans laquelle les phases d’exploitation, de transformation et de reconversion...

- 28 mai 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Le patrimoine naturel

La communauté - Auteur : Tamara Chipperfield et Kiki Aravopoulos,

Patrimoine et harmonie : l’intégration des paysages naturels et culturels

Depuis environ 11 000 ans, le panorama ontarien témoigne de l’évolution de notre culture. Aujourd’hui, les paysages naturels de l’Ontario sont, dans leur grande majorité...

- 28 mai 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Erin Semande,

Préserver le patrimoine pour assurer l’avenir

Goderich se dresse sur les rives du lac Huron, à proximité de l’embouchure de la rivière Maitland. Celle que l’on surnomme « la plus jolie...

- 28 mai 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Joe Lobko et Megan Torza,

La renaissance de Wychwood Barns

L’Artscape Wychwood Barns – situé près de l’avenue St. Clair Ouest et de la rue Bathurst à Toronto – est né de la transformation de...

- 28 mai 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement - Auteur : L.A. (Sandy) Smallwood,

Rejeter le passé

Quand un vieux bâtiment est démoli, nous ne perdons pas simplement une structure. Nous perdons un peu de notre histoire. Les murs de fondation et...

- 12 févr. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Kathryn McLeod,

Le patrimoine de la 401

L’autoroute 401, qui s’étend de Windsor à la frontière du Québec, est l’une des voies les plus encombrées d’Amérique du Nord. Toute personne ayant voyagé...

- 12 févr. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Rebâtir sur les fondations du passé

L’Est de l’Ontario comporte un vaste éventail de maisons historiques toutes aussi impressionnantes les unes que les autres. Certaines de ces maisons – détenues et...

- 12 févr. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Glenda Jones,

Quand l’usine devient musée

La lourde porte en chêne du musée du textile de Mississippi Valley situé à Almonte, dans l’Est de l’Ontario, s’ouvre en silence, comme elle le...

- 12 févr. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Wayne Kelly et Kathryn McLeod,

Les trésors de l’Est de l’Ontario

Territoire élu des peuples autochtones depuis 7 000 ans, l’Est ontarien recèle aujourd’hui un riche patrimoine. La région s’est transformée graduellement, sous l’influence des Français...

- 12 févr. 2009

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Ellen Kowalchuk,

L'histoire de Rockwood

Derrière l’imposante façade de la villa Rockwood, à Kingston, s’est déroulée l’histoire des services de santé mentale de l’Ontario. Construite en 1842 pour servir de...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Le caractère de la conservation intégrée

C’est dans son traité de 1947 intitulé « The Past in the Future », que l’architecte et historien John Summerson (1904-1992) offre cette description d’un...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Erik R. Hanson,

Renouveau du patrimoine inestimable de Peterborough

Pour créer un centre-ville sain, le plus difficile est de convaincre les gens d’y habiter. Bien que de nombreux et magnifiques édifices patrimoniaux ornent le...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Le patrimoine de la foi : Les lieux de culte de l’Ontario

En 2006, la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien a commencé à dresser l’inventaire des bâtiments datant d’avant 1982 spécifiquement construits dans l’ensemble de la province pour...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Marcus R. Létourneau,

Patrimoine pérenne de Kingston

La ville de Kingston est située à un endroit stratégique, à mi-chemin entre Montréal et Toronto, un endroit où le lac Ontario rencontre l’extrémité ouest...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Beth Anne Mendes et Erin Semande,

Souvenirs du Collège Alma

Le mercredi 28 mai 2008, vers le milieu de l’après-midi, le Collège Alma de St. Thomas a été réduit à l’état de ruine fumante. La...

- 11 sept. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Comprendre la conservation intégrée

Dans le cadre des efforts de conservation des biens patrimoniaux, la recherche d’un nouvel usage peut représenter à la fois le plus grand défi et...

- 12 juin 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Thomas Wicks,

Une renaissance du patrimoine du Nord de l’Ontario

L’avènement du chemin de fer a permis de relier cette région autrefois isolée au reste de la province, à la fi n du 19e siècle...

- 12 juin 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Denis Héroux,

Travailleurs aventureux recherchés pour des sites lointains – logement fourni

L’exploration, l’établissement et le développement dans le Nord de l’Ontario étaient motivés par l’exploitation des ressources naturelles de la région – principalement les fourrures, le...

- 12 juin 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Icônes du Nord

L’imposant chevalement d’extraction de la mine McIntyre de Timmins. Le blockhaus de Clergue et la poudrière de Sault Ste Marie. L’église anglicane Saint-François d’Assise de...

- 12 juin 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les paysages culturels - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Le district minier historique de Cobalt – une ressource communautaire

Au début du 20e siècle, Cobalt était un petit camp de bûcherons isolé. En août 1903, deux bûcherons – James McKinley et Ernest Darragh –...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les objets culturels - Auteur : Kathryn Dixon,

Les amis de la Fiducie

Tout au long de ses quarante années d’existence, la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien a noué de solides partenariats avec des collectivités locales. Parmi ces partenariats...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les arts et la créativité

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Gordon Pim,

Levée du rideau : Redécouverte du théâtre Winter Garden

En décembre 1913, le théâtre de la rue Yonge appartenant à la société Loew – le joyau canadien du prestigieux empire Loew – ouvrait ses...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Assumer le passé

Les bâtiments, structures et paysages qui composent notre patrimoine culturel sont le résultat de l’influence réciproque et complexe entre les individus et les lieux au...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Avez-vous vu ce bâtiment?

En novembre 2007, la maison Sir Aemilius Irving à Hamilton a été démolie par son propriétaire et a fait place à un nouveau bâtiment. Malheureusement...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Beth Hanna,

L’école Enoch Turner – le legs d’un citoyen

Lorsque la province de l’Ontario adopta la Loi sur les écoles communes en 1847, les municipalités obtinrent le pouvoir d’instaurer des taxes pour financer l’enseignement...

- 14 févr. 2008

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Laura Hatcher,

Cela n’aura pas été en vain

Erigée à Glengarry en 1821, l’église de Saint-Raphaël a été l’une des premières églises catholiques romaines de l’Ontario. Construite sous la férule d’Alexander Macdonell, le...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Construire de la valeur

Qu’est-ce qui est le plus viable écologiquement : un arbre de Noël artificiel ou un arbre véritable? C’est la devinette préférée des environnementalistes et elle...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Les principes directeurs d’une architecture viable

À la fin des années 1990, le ministère de la Culture de l’Ontario a présenté Huit directives en matière de conservation des biens du patrimoine...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement - Auteur : Sean Fraser et Karen Abel,

Dans Sheppard’s Bush

Charles Sheppard (1876-1967) arriva dans la ville d’Aurora en 1921, après avoir fait fortune dans l’industrie du bois d’œuvre dans le comté de Simcoe. Brooklands...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Robert Plitt and Sean Fraser,

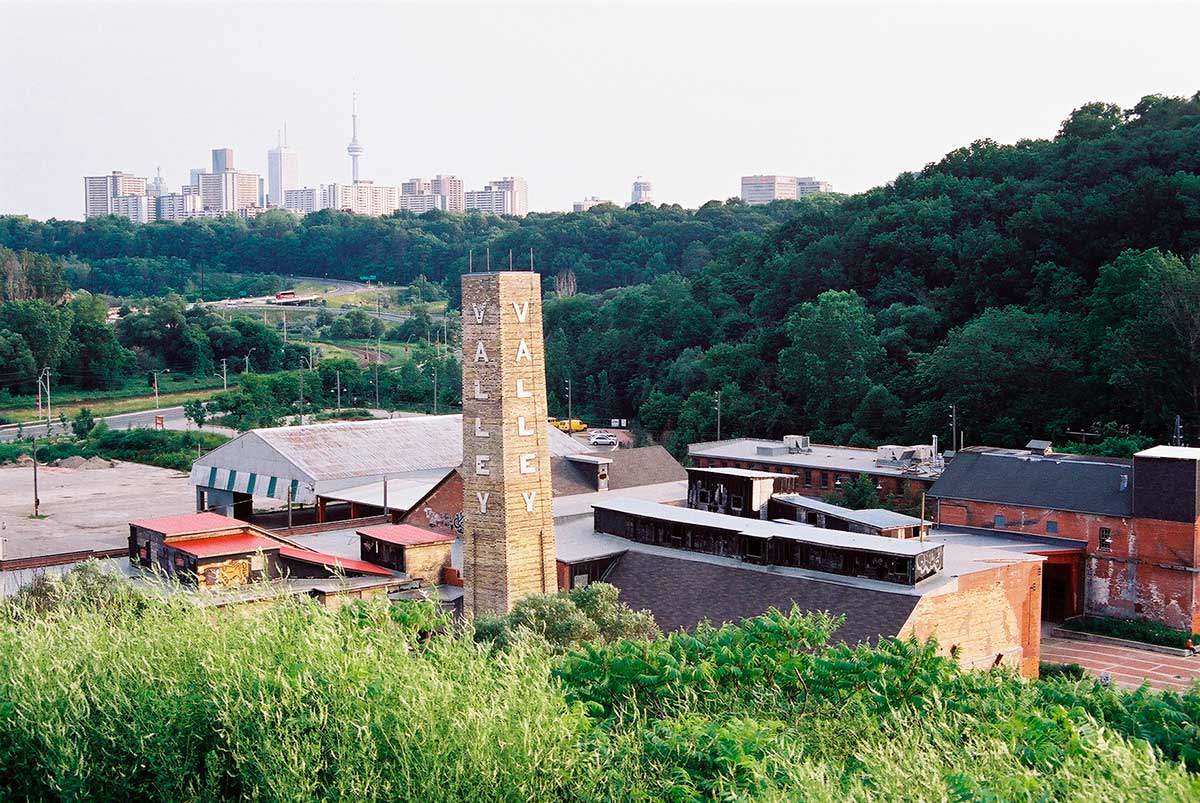

Evergreen Brick Works : L’espace repensé

Evergreen – organisme de bienfaisance – bâtit un pont entre nature, culture et collectivité dans les espaces urbains. Avec la revitalisation du site Don Valley...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Beth Anne Mendes,

À la découverte du mouvement City Beautiful

Le 25 juillet 2007, une plaque provinciale a été dévoilée par la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien et la ville de Kapuskasing, pour commémorer le plan...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Mythe ou réalité : Combattre les idées reçues autour du thème de l’écologie – Vers une architecture plus durable

Viable : de nature à être maintenu à un certain taux ou niveau . . . maintien d’un équilibre écologique en évitant un épuisement des...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

L'environnement

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Alex Speigel,

Viabilité des anciens bâtiments : le point de vue d’un promoteur

Le réaménagement permet d’envisager la rénovation de notre tissu urbain de façon saine et durable, comme l’illustre la conversion de trois bâtiments de Toronto en...

- 15 nov. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Éloge des vieilles fenêtres

Façade : un mot à double sens. En architecture, il s’agit de la façade d’un bâtiment. En littérature, la plupart du temps, il désigne une...

- 10 mai 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Consolider nos succès

Les servitudes protectrices du patrimoine de la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien protègent certains des sites du patrimoine les plus importants. Une bonne administration des propriétés...

- 10 mai 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Kathryn Dixon,

L’histoire de la Maison Barnum

La maison Barnum, située au nord de la route 2 (Danforth Road), à l’ouest de Grafton, revêt une importance historique en raison de ses liens...

- 10 mai 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Beth Hanna,

Les verbes de la conservation

Une génération précédente a parlé de la règle des trois verbes « Lire », « Écrire » et « Compter ». Ils constituaient la base...

- 10 mai 2007

- Le patrimoine militaire

Les bâtiments et l'architecture - Auteur : Susan Ramsay and Marnie Maslin,

Maison-Musée et Parc du Champ de Bataille – Un pionnier dans l'histoire de la préservation

Niché sous l’escarpement du Niagara et situé dans un parc communiquant avec le sentier Bruce, le lieu historique national de la maison-musée du champ de...

- 10 mai 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Prise d’initiatives en matière de planifıcation du patrimoine municipal

Que se passe-t-il dans votre collectivité? Suite aux modifications importantes apportées à la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario en avril 2005 et au renforcement...

- 15 févr. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Kiki Aravopoulos,

À la découverte du Country Heritage Park

En mars 2006, la Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien a acquis une servitude du patrimoine culturel sur le Country Heritage Park. Située à Milton, cette attraction...

- 15 févr. 2007

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les objets culturels

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Romas Bubelis et Nick Holman,

La conservation du patrimoine sur le pas de la porte

Le terme « porte-cochère » rappelle l’Europe et tire ses humbles origines des portails couverts qui menaient à une cour intérieure suffisamment grande pour accueillir...

- 15 févr. 2007

- Le patrimoine Noir

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Le patrimoine naturel - Auteur : Gordon Pim,

Patrimoine « numérique »

Le patrimoine de l’Ontario est un immense et complexe jeu de patience. Chaque pièce du patrimoine considérée individuellement crée un ensemble … une espèce de...

- 07 sept. 2006

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Louise Burchell,

Sauver le moulin de Spencerville – Préserver le patrimoine communautaire

Le moulin de Spencerville, un beau moulin à grain et à farine en pierre de taille, se trouve sur les bords de la rivière Nation...

- 07 sept. 2006

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Les objets culturels - Auteur : Erin Semande,

La biographie d’ une demeure : Si ces murs pouvaient parler!

Les recherches sur l’histoire familiale sont un passe-temps populaire pour de nombreuses personnes qui veulent découvrir le passé unique de leur famille et savoir comment...

- 16 févr. 2006

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté

Réutilisation adaptative - Auteur : Sean Fraser,

Célébrons notre patrimoine culturel! Mode d’adaptation des bâtiments du patrimoine

Bien que le patrimoine maintienne un grand nombre d’entre nous occupés à longueur d’année, la Fête du patrimoine est célébrée chaque année le troisième lundi...

- 16 févr. 2006

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Gordon Pim,

Images du passé

Un flash de phosphore. Une odeur de fumée. Et l’image est dans la boîte. Cela fait plus de 150 ans que les photographies relatent nos...

- 16 févr. 2006

- L'archéologie

Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les objets culturels

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Romas Bubelis,

Un papier peint historique : À la découverte de sa face cachée

Les papiers peints ont fait leur apparition au Canada dès le milieu du 17e siècle. Ces plus vieux papiers étaient peints à la planche, à...

- 16 févr. 2006

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : Tim Mallon,

Les musées locaux, clé de la réussite des petites villes

Dix-huit années durant nous avons, ma femme et moi, élevé nos deux fils dans la Ville de Richmond Hill située au Nord de Toronto. Au...

- 16 févr. 2006

- L'archéologie

Les bâtiments et l'architecture - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

Nouvelle de dernière heure : Le sauvetage de notre premier parlement

Le 21 décembre 2005, on a annoncé que le site des bâtiments du premier parlement ontarien avait été sauvé. Le gouvernement de l’Ontario, en association...

- 08 sept. 2005

- L'archéologie

Les bâtiments et l'architecture - Auteur : Dena Doroszenko,

Déterrer le passé : Découvertes à la maison Macdonell-Williamson

Construite en 1817, la maison Macdonell-Williamson, située dans l’Est de l’Ontario, reflète les aspirations et les ambitions de John Macdonell, un négociant en fourrure à...

- 08 sept. 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

La communauté - Auteur : David Cuming,

Impulsion donnée à la conservation du patrimoine

Il y a trente ans, lorsque la Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario était encore nouvelle, j’étais depuis environ un an un jeune planificateur qui...

- 08 sept. 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

Un toit solide : Demeurer au faîte de la préservation du patrimoine

Lʼextrait suivant est tiré de Well-Preserved : The Ontario Heritage Foundationʼs Manual of Principles and Practice for Architectural Conservation (Troisième édition révisée), par Mark Fram...

- 08 sept. 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Barbara Heidenreich et Jeremy Collins,

Nouvelles servitudes protectrices du patrimoine naturel

Refuge John Edward (Ted) Greenwood Le 30 mars 2005, la Fondation du patrimoine ontarien a reçu, de Mary Greenwood, de Nakara, en Australie, une parcelle...

- 08 sept. 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Le patrimoine naturel

La communauté

Les paysages culturels - Auteur : Richard Moorhouse et Beth Hanna,

La nouvelle Loi sur le patrimoine de l’Ontario : L’évolution de la conservation du patrimoine

Le cadre législatif de la conservation du patrimoine en Ontario vient de changer de façon radicale. Le 28 avril 2005, la Loi modifiant la Loi...

- 19 mai 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Larry Wayne Richards,

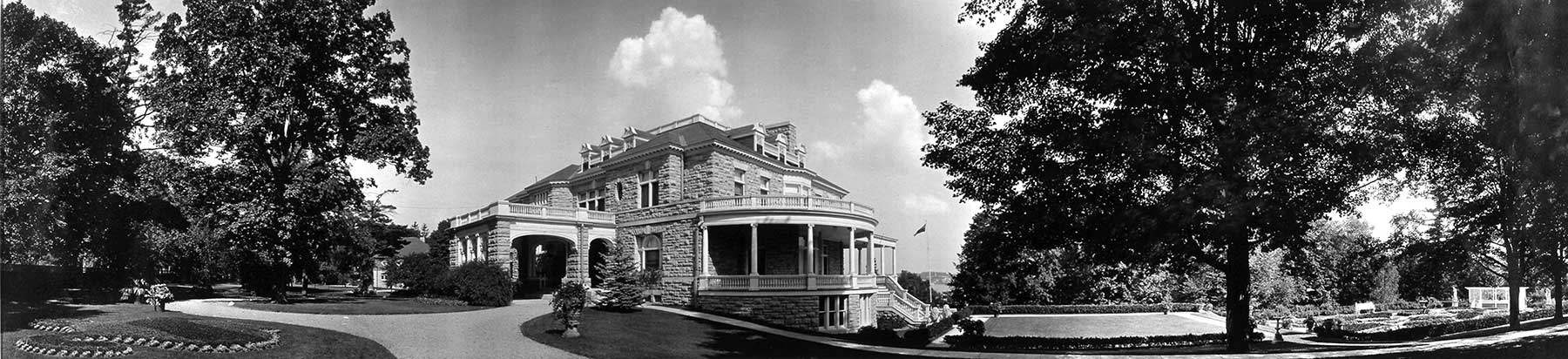

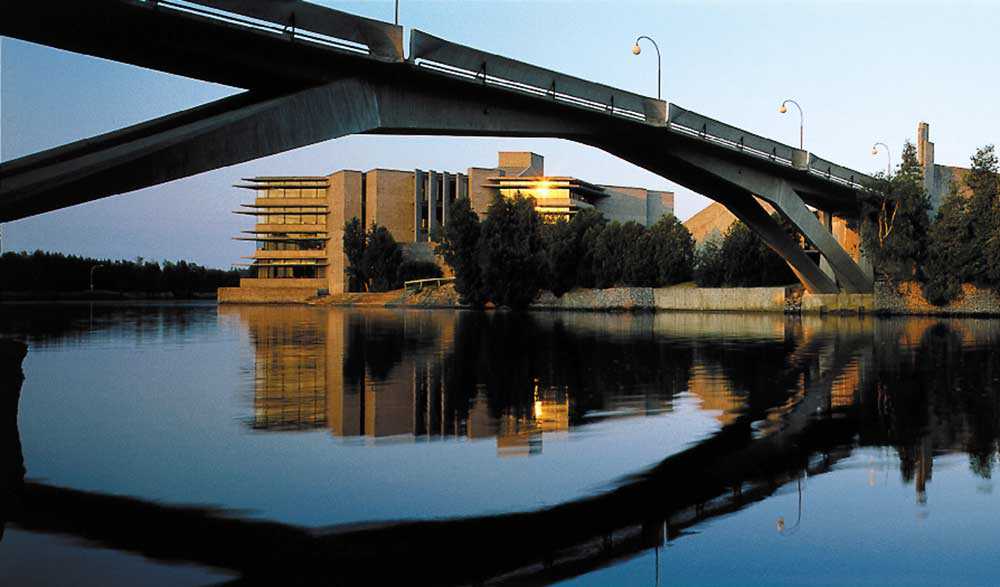

Université Trent – sous le microscope moderniste

Dans tout le monde développé, on prête attention au patrimoine architectural de l’ère moderne. Des organismes comme le Centre pour le patrimoine mondial de l’UNESCO...

- 19 mai 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les outils pour la conservation - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

Les superstructures : Ossature des bâtiments patrimoniaux de l’Ontario

Dans le dernier numéro, nous avons traité de lʼimportance de fondations solides pour la préservation des structures patrimoniales. Dans ce numéro-ci, nous voyons le rôle...

- 19 mai 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

Leidra Lodge – Une nouvelle servitude protectrice du patrimoine

June Ardiel a été une protectrice et un chef de file de la communauté artistique ontarienne pendant toute sa vie. Elle a écrit un livre...

- 19 mai 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Moiz Behar,

Le visage changeant du patrimoine : Le style international – Le Centre Toronto-Dominion de Toronto

Pendant le deuxième quart du 20e siècle, qui suivit la Première Guerre mondiale, l’Europe vit la naissance d’un important mouvement en architecture. Ce mouvement «...

- 19 mai 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

Les objets culturels - Auteur : Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien,

La collection Homewood

Sur la route 2, en direction est, entre Brockville et Prescott, vous trouverez, très en retrait, le musée Homewood, de style « Georgian ». Une...

- 12 févr. 2005

- Le patrimoine Noir

Les bâtiments et l'architecture - Auteur : Wayne Kelly,

Dans la Case de l’oncle Tom

Dans un coude de la rivière Sydenham, près de la ville de Dresden, se dresse le Site historique de la Case de l’oncleTom. Le musée...

- 12 févr. 2005

- Les bâtiments et l'architecture

- Auteur : Sean Fraser,

The Sharon Temple and the heritage of faith

While most of Canada celebrates Heritage Day on the third Monday in February, Ontario celebrates Heritage Week. The theme developed for Ontario Heritage Week 200...

- Accessibilité

- Déclaration concernant la protection de la vie privée

- Conditions d'utilisation

- © Imprimeur du Roi pour l’Ontario, 2023

- Photos © Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien, sauf indication contraire.

- Accessibilité

- Déclaration concernant la protection de la vie privée

- Conditions d'utilisation

- © Imprimeur du Roi pour l’Ontario, 2023

- Photos © Fiducie du patrimoine ontarien, sauf indication contraire.